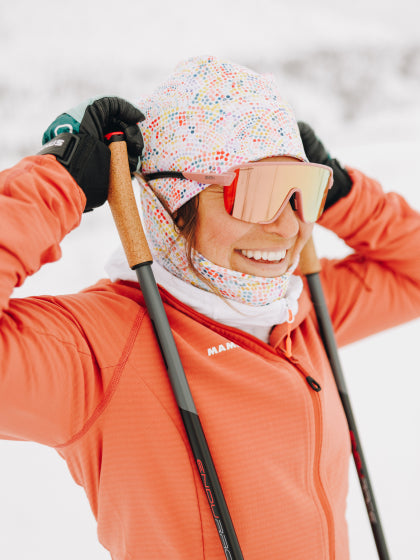

photos by alison vagnini / 📍 loveland ski area

Words from a Ski Patroller

Last Spring, the patrol ladies of the Loveland Pass Ski Area let photographer Alison Vagnini tag along with them to capture a typical day in their life on hill. From the 5am wakeup to tackling avalanche mitigation with your best friends, this job is no small feat and isn't for the faint of heart.

Read on for a first-hand perspective from ski patroller, Allison Perry.

words by allison perry ✍️

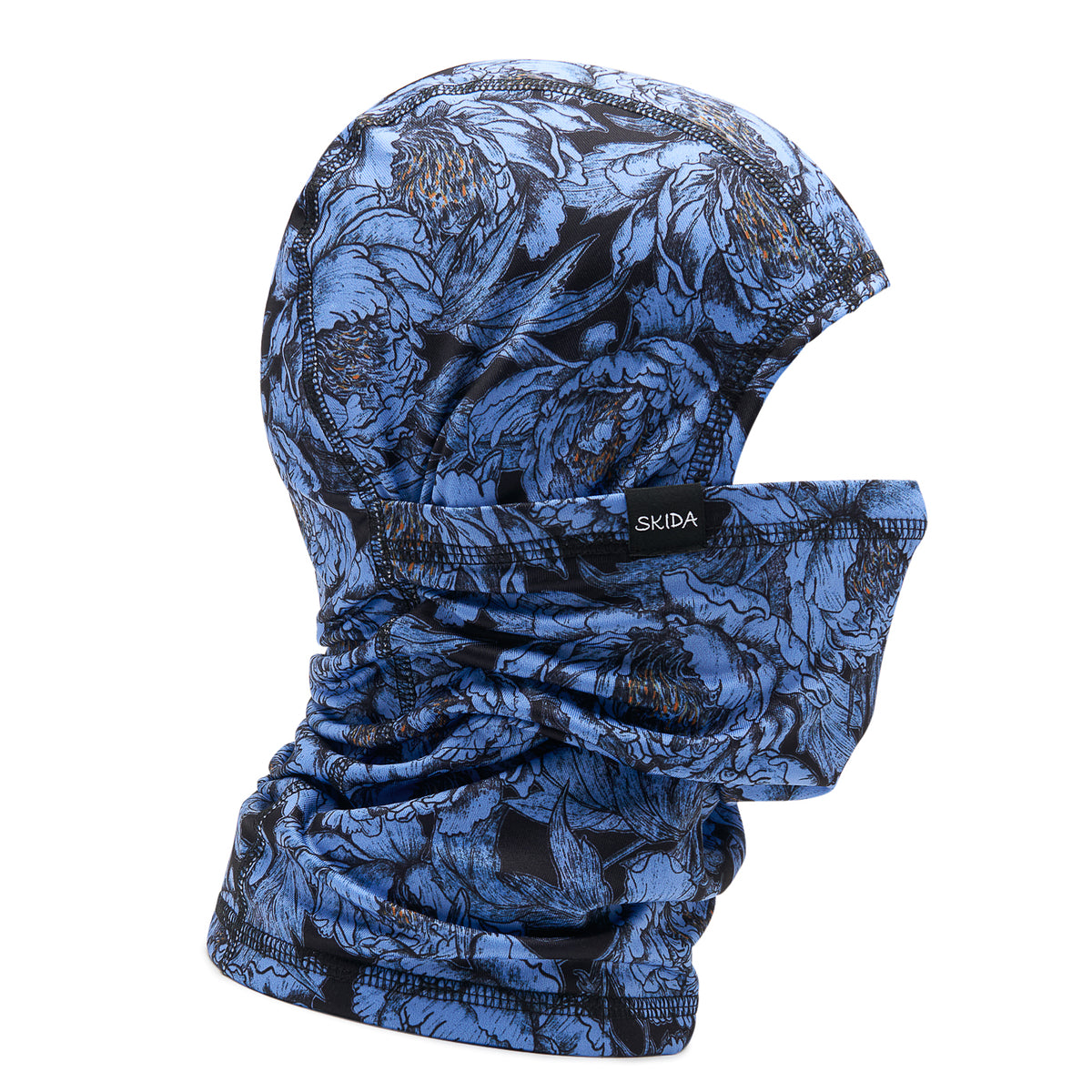

There’s a lot of things nobody warns you about when you decide your life’s dream is to become a professional ski patroller, as I did, in 2015. For example, every ring tone on your phone will be ruined because waking up at 5am to “By the Seaside”, “Reflection” or a series of chimes and beeps when it’s absolutely frigid and still dark outside is a unique kind of torture, reminiscent of being woken up by mom or dad to go to school. I DON’T WANNA! During patrol season I keep a beanie on my bedside table because I often put one on before exiting my cocoon of comforters to “preheat” for the transition of pajamas to base-layers. When you live at 10,000 feet in a big old house heated by a wood stove and have to clock in at the base of a ski area forty five minutes away by 7am, this is simply your new reality.

Prior to being a patroller I also had no idea that a four cylinder turbo engine can shave ten to fifteen minutes off a high altitude hill commute; that choosing the right windshield wipers is literally a matter of life or death; or the pure joy of being the first car stuck behind a line of snowplows, as they fan out four deep across the highway in a whiteout blizzard, doing 40 under the speed limit in your very own parade of lights atop newly scraped road.

Before I became a ski patroller I also didn’t know the bliss of riding a chairlift up to the shack after sweeps on a perfect spring evening, clad only in a patrol vest, t-shirt and sunshine, wondering “how on Earth did I get so lucky”? Not one season goes by that I don’t tear up at least one day, when I have the chair to myself, the mountain is empty, and the only chatter on my radio is the symphony of my co-workers calling trails clear. I marvel at how my job is literally skiing with my friends, as I sniffle and blink. “I’m just exhausted” I tell myself because big girls don’t cry.

"Not one season goes by that I don’t tear up at least one day, when I have the chair to myself, the mountain is empty, and the only chatter on my radio is the symphony of my co-workers calling trails clear."

As I mentioned, we start a typical day at 7am gearing up at our lockers, which for me involves putting on enough layers to evoke Ralphie from A Christmas Story even if it’s 35 degrees outside because I generally run hypothermic. We boot up during morning meeting where we get weather and avalanche forecasts, projects to look forward to - roping trails, digging out and lifting pads, ferrying medical equipment around, avalanche mitigation, to name a few - and often enjoy laughs and the semi-occasional shenanigan. One of the more infamous pranks on my current patrol (Loveland Ski Area) involved a patroller lowering our Director’s rolling chair by about a centimeter a day until, weeks later, he almost kneed himself in the face. We find camaraderie in both expected and unexpected places and it is the glue that holds any patrol together.

After meeting it’s time for trail and equipment checks, central dispatch signs on for the day (I do this once a week) and guests start to trickle in and line up. If we get really lucky we have just enough new snow that we can ski fresh lines on trail checks, but not enough new snow to have to use explosives to mitigate the terrain and then immediately open it to guests. Contrary to popular belief, patrollers do not spend very many days just skiing powder. We feel just as blessed as you when we get to send an untracked line. And that line is often the reward for weeks upon weeks of skiing in the worst conditions you could ever dream up: vertigo-inducing whiteouts and wind events; Sastrugi (look it up, it is not a pastry you can order in an Austrian bakery); Man-eating Sastrugi; Man-eating moguls; Man-eating wind slab (Mother Nature only eats men, it’s science); velcro flats; bullet proof ice; frozen chicken-heads; ACL-destroying hot brown pow; dirt; rocks; logs; avalanche debris and facets facets facets. My next job is simply going to be making up names for the other thousand variations of snow conditions not listed herein. Smurf Hats? Murder-roy Corduroy? Pucker Slush? Groomer? Oh wait, that one’s real.

"We find camaraderie in both expected and unexpected places and it is the glue that holds any patrol together."

Snow and skiing make up a large portion of our day-to-day, but our first and most important function, far above and beyond the sexier aspects of the job like throwing bombs and running toboggans, is emergency medicine. Patrollers usually fall into one of two (or both) categories of first responder: Outdoor Emergency Care Technician (“OECT”) or EMT (y’all know what that one is). Some of us, yours truly included, are EMTs with IV certifications and I would be lying if I said I didn’t love sticking needles in people. Advanced EMTs are rare but valuable. Paramedics are also part of any patrol team - some work on the hill as patrollers, some primarily work in the Aid Room, but they are a wholly instrumental part of keeping people...alive, and in helping us hone our skills.

Before I was a ski patroller I had never seen much blood. I hadn’t gingerly touched a smashed face, dressed a bone sticking out of skin, gasped at a hematoma so big it turned into a bruise measured in feet, looked at someone’s femur through a giant laceration, or put a child on a backboard in front of their parents, wanting to cry along with them but knowing that there was no universe in which I could do that to them or their kid. I had not yet been vomited on or swung at (head injuries make people combative) and CPR was more abstract theory than reality. The first life I ever got a save was my sixth season as a ski patroller, third time working a code (a CPR call) and it was one of the calmest most anti-climactic scenes I’ve ever been on. And one of the most profound examples of how good training and good teamwork matter more than anything else. Period.

"...at the end of yet another day, another week, another month and another season, wondering how on Earth did I get so lucky?"

Before I did this job I didn’t know how strong I could be. And that has nothing at all to do with how many pounds I can lift (few) or how many miles I can run (fewer).

Every year since 2019 I’ve said “this is my last year patrolling” and I’ve meant it. I’m tired. My feet are mangled. I have $71 in my savings account and I’ve been in three car wrecks to and from work that could have killed me - the last one resulting in aforementioned four cylinder turbo engine and being in debt up to my eyeballs until I’m 159. I’m only 42. Someday, I want to travel to a place that isn’t Utah. I dream of doing kick turns on my 185s without poles only to show off, rather than out of necessity.

Every year since I last said, “his is my last year patrolling,” yet I somehow find myself starting the day in a beanie in the dark and tearing up (or not) on a chairlift after sweeps, at the end of yet another day, another week, another month and another season, wondering how on Earth did I get so lucky?